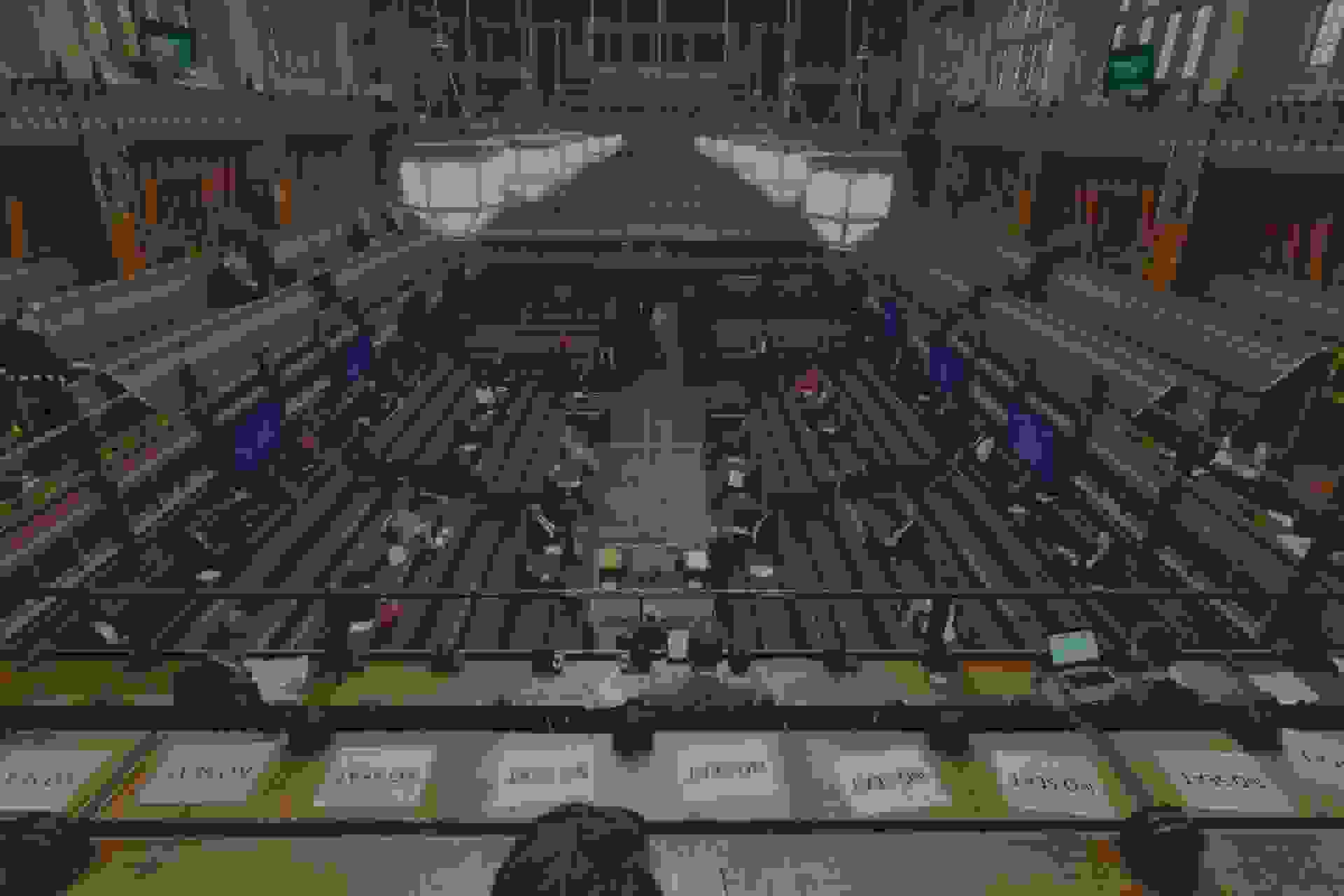

News / Parliament Matters Bulletin: What’s coming up in Parliament this week? 14-18 July 2025

MPs will consider a rare privilege motion relating to a request from the Omagh Bombing inquiry, while the Conservatives will choose the topic for Tuesday’s Opposition Day debate. Select Committees will question Cabinet Ministers on welfare reform, the NHS Plan, foreign policy, national security, and policy announcements made first to the media rather than Parliament. The Deprivation of Citizenship Orders Bill will complete its Commons stages. Peers will scrutinise bills on renters’ rights, employment, and planning. MPs will debate Statutory Instruments on media mergers, murder sentencing, and energy costs, and will vote on extending interest registration rules for MPs’ staff. Backbench MPs will lead debates on giving every child the best start in life, the Global Plastics Treaty and end of life care. The House of Lords will debate the Strategic Defence Review. → We value your thoughts. Please click here to let us know what you think of the Parliament Matters Bulletin in our reader survey.